Last week was a sad and sobering week.

Prince, the remarkably talented artist, died at the young age of 57.

The world knows Prince! And if for some very strange reason you didn’t before last week, you certainly do by now – given all the touching and well deserved remembrances since last Thursday.

The world may not know Neal Gabler, the author of the Atlantic article that went viral last week – “The Secret Shame of the Middle-Class.”

But nearly half of Americans can relate to his financial story.

In the above-referenced article, Neal came out as being one of the 47 percent. Meaning: He is one of the people the Federal Reserve Board references in its 2013 study as being unable to come up with $400 for an emergency. Even though he has written five books, hundreds of articles, received numerous awards and fellowships, and even sold a screenplay to Martin Scorsese.

Said differently, because of his education and profession, he doesn’t look like someone who is financially vulnerable and unstable.

It may seem odd as heck to mention Prince and Neal in the same post. And in no way am I comparing Prince’s genius and prolific body of work that spans four decades with this one insightful article from Neal.

Yet, the cultural impact of Prince’s work and Neal’s personal essay have this in common: They prompt questions that serve as a gateway for discussing important social issues – for perceived outliers.

Prince’s “difference” could be seen and heard. Whether a contrarian by nature or by design, he defied labels and would purposefully go “left” when everyone else went “right.” Sending the signal that being different was okay; that risk taking is innate.

Not so with Neal. What made him different couldn’t be seen by anyone other than his wife, children, and creditors who were acutely aware of his financial struggles. His difference wasn’t (isn’t) socially acceptable. He wasn’t just broke – he was a highly educated, accomplished, middle-aged, broke white man.

Not your typical picture of poor, financially insecure and vulnerable.

Some in the media have lambasted Neal saying his travails are entirely his fault. Sure, his personal choices played a role in his predicament. But how is he any different than you and me?

Even if you can’t relate to him and his family not having $400 for an emergency…

- can you relate to the notion that you’ve done all the right things and never, ever “figured you wouldn’t earn enough?”

- can you relate to hoping and waiting for things to turn around for so long that by the time you face the music and do what you’ve been avoiding, you realize you waited a beat too long?

- can you relate to only forecasting how great things will be and paying little attention (if any) to what can possible go wrong?

We all make choices. Sometimes we like and embrace the outcomes of those choices; other times not so much. At all times, though, those choices are in the context of our personal circumstances and the context of what is happening on a larger, social plane.

There is always more to what you see than what is in front of you. So, I’m grateful to Neal for his willingness to share his story. By his own admission, he kept quiet about his financial struggles because it was a source of shame.

Dealing with financial stress is a “silent” killer of spirits, ideas, creativity, and innovation.

Prince’s death is deeply sad.

Neal’s story is deeply thought-provoking.

It’s pretty darn sobering to know that millions of people are living on the financial brink – that a $400 emergency could trigger an unimaginable downward spiral. If like him, you are (or have) been in the same boat suffering in silence alone. First, that sucks. Sorry.

Second, this isn’t a situation where this is other people’s problem (or yours, if I’m speaking to you) to bear in isolation. Emergencies happen all the time. Financial rough patches are likely to increase and last longer as the economy shifts to more people unwillingly becoming freelancers. If financial emergencies and rough patches happen to a significant number of people at the same time, that doesn’t just affect the individual, it impacts us all.

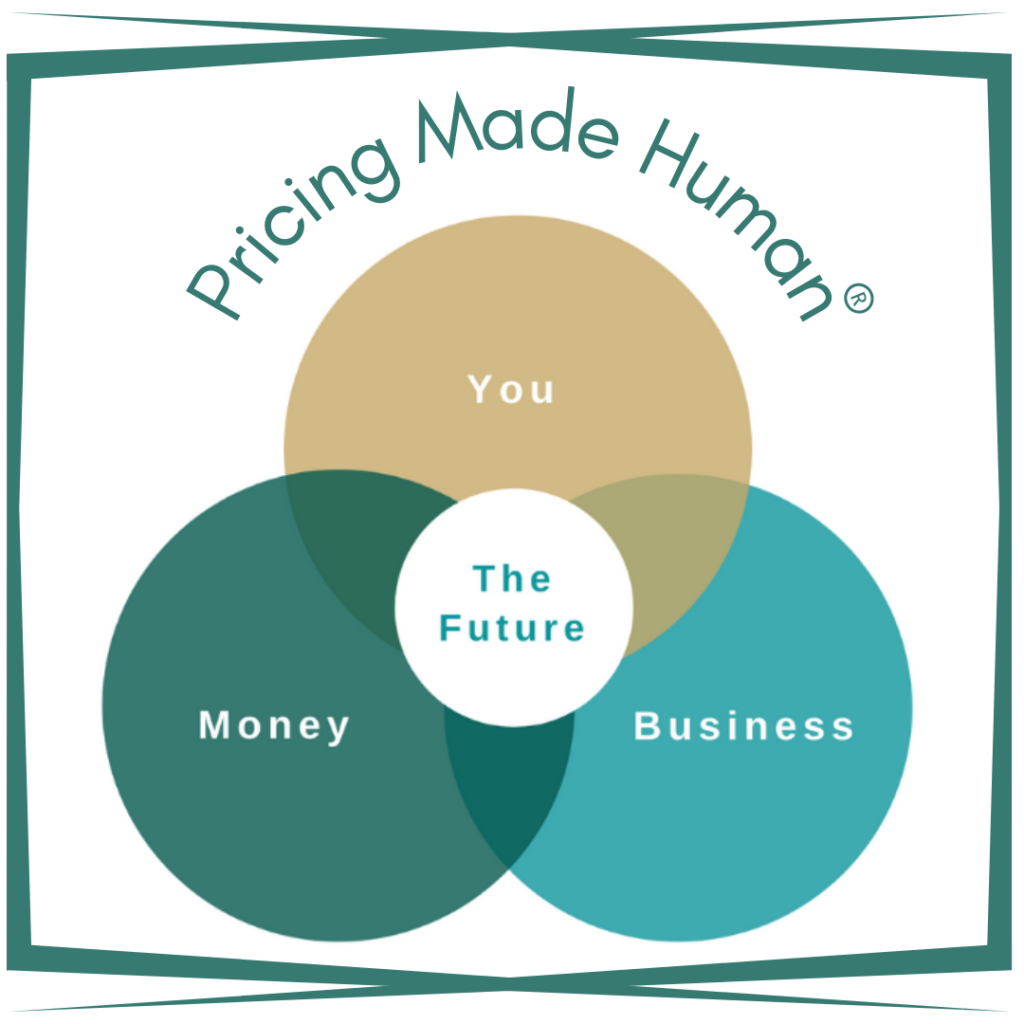

What is currently a secret shame needs to be a clarion call for change in how we view the intersection between money, personal choices, economic policy and financial innovation.